Chaining Language Model to Algorithm: Generative AI Series Part 5

Introduction

In my previous post on the Generative AI series, one problem with the language model, namely “the knowledge cutoff” issue, and we learnt about a technique called RAG that helps to solve the problem. Continuing further, here we look at another problem of the language models: Hallucination.

Hallucination is the problem that makes large language models arrogant 😒 about their answers, where they insist on validating their answer even if the argument is logically flawed. For instance, if you prompt an LLM to find out the answer to a multiplication of two three digits numbers, say 12346 x 98754 and show the output step by step, it will show you some mathematical steps that look correct but actually are not. It is unlikely that it will even output the correct answer 1219216884 in this case. I prompted the same to the Claude LLM, it responded back with

Assistant: Sure, let's multiply 12346 by 98754 step-by-step:

Step 1: Write the numbers one under the other, aligning the ones digits.

98754

12346

-----------

Step 2: Multiply the bottom number (12346) by each digit of the top number (98754) from right to left.

12346 x 4 = 49,384 (Write this partial product on the next line)

12346 x 5 = 61,730(Write this on the next line, shifting one place to the left)

...

Step 3: Add the partial products vertically.

111,114

86,422

61,730

49,384

-----------

1,218,650,664

Therefore, the multiplication of 12346 and 98754 is 1,218,650,664.As you can see, it returns back with some “near-correct” steps, but the final answer is wrong.

In this post, we will explore ways to address this kind of problem with generative AI models.

Solving Hallunication: Introducing Tools

The fundamental issue underlying the hallucination problem is that the knowledge of the LLM-type AI models is fuzzy and probabilistic in nature, like us. Hence, it does not actually understand the logical deductions or steps involved with a multiplication problem, but rather it is simply trying to autocomplete the sentence in a reasonable way.

To solve this, let us take a step back and think about how we humans would solve the problem: since then we can aim to mimic the human behaviour in the AI. As a human, you might possibly use a calculator for this (unless, of course, you are a nerd 🤓 and you love doing multiplications ✖️). So, we will allow our AI system to use a calculator-like function for the same.

So now, the idea is as follows:

Design a prompt for the LLM which describes the calculator function and its arguments.

When we ask the LLM the query about the multiplication result, it responds in a specific way by showing that it is using the calculator function with proper arguments.

Here, we stop the LLM and intervene. We parse the output of the LLM using Regular Expression (if you don’t know what it means, check out this cool website) and get the arguments.

Then we call a normal computer code to perform the calculation for us. This can be your typical software program written in programming languages (e.g. - Python 🐍, Golang 🏃, Java, etc.)

Once the computer code runs, we pass the result in a nicely formatted string and ask the LLM to continue generation from there on.

This entire system of using external software code along with the powerful natural language capabilities of LLM is called Function Calling.

Designing Prompt for Function Calling

The system prompts for a function calling generative AI system usually uses a specific template.

We start by saying:

You are a helpful chatbot …. In this environment, you have access to the following tool. You may use it by responding in the format

<function_call>

<function_name>Give the name of the function you want to use</function_name>

<input><{parameter name}>value of the parameter</parameter_name> </input>

</function_call>

...This is the initial setup before we describe the function (or tool) to the generative AI. This prompt asks the LLM to respond in a specific format if it uses a function, this helps us in parsing the output of the LLM when we intervene.

Once we have this initial prompt added, then we add the description of the function, namely our calculator function.

<function>

<name>run_calculator</name>

<description>A function that performs basic mathematical calculation operation.</description>

<arguments>

<operation>

<type>string</type>

<description>The binary operation to perform between two numbers, must be one of +, -, *, / </description>

</operation>

<first_number>

<type>number</type><description>The first number</description>

</first_number>

<second_number>

<type>number</type><description>The second number</description>

</second_number>

</arguments>

</function>Note that, this above prompt describes the calculator function in detail. It tells that the function name is “run_calculator”, provides a description of what it does, and then describes its three arguments. The first argument is a string denoting the binary operation (addition, subtraction, multiplication or division, what to perform), and the next two arguments are the two numbers before and after the binary operation symbol.

There are multiple ways to generate it. The following are two extreme ideas:

We writing this prompt entirely manually.

We write the actual code for this run_calculator program (or function/tool). We then use the code comprehension ability of LLM to generate a docstring for the function (i.e., basically a human-readable documentation for the function and its arguments). Usually, these docstrings come in a predefined format (e.g. - JsDoc, NumpyDoc, Doxygen, these are some of the popular ones you may have heard about). These predefined formatted docstrings can then be easily parsed and converted into the format required by the above prompt. Here, the entire prompt generation process itself is automated.

Usually, people tend to prefer a middle ground. They begin with an auto-generated tool description for the prompt and then tweak it to get the most performance out.

Parsing Function Calling Response

Given the query “What is the result of 12346 times 98754?”, the LLM now responds according to the format given in the system prompt.

Assistant: Sure, to multiply 12346 by 98754, we can use the provided tools as follows.

<function_call>

<function_name>run_calculator</function_name>

<input>

<operation>"*"</operation>

<first_number>12346</first_number>

<second_number>98754</second_number>

</input>

</function_call>Note that, the LLM might continue to say something more. Here, a useful setting “stop sequence” might be useful. See more in my previous post.

Usually, a single RegExp expression can give you all the required things, i.e. the name of the function and its parameter values. For example, in Python, you can use <(.*?)>(.*)</\1> (To verify this, copy the response of the LLM into this RegExp testing website.) For the sake of completion, let me break it down. The first part, <(.*?)> matches any tag-like string, yielding the name of the parameter (i.e., operation or first_number or second_number). The middle part captures the actual value of the parameter. And, the final part ensures that the tag captured in the first part has a closing tag as well.

So, at the end of this step, your software application will contain three variables as follows:

string op = "*";

number firstNum = 12346;

number secondNum = 98754;Building the Calculator Function

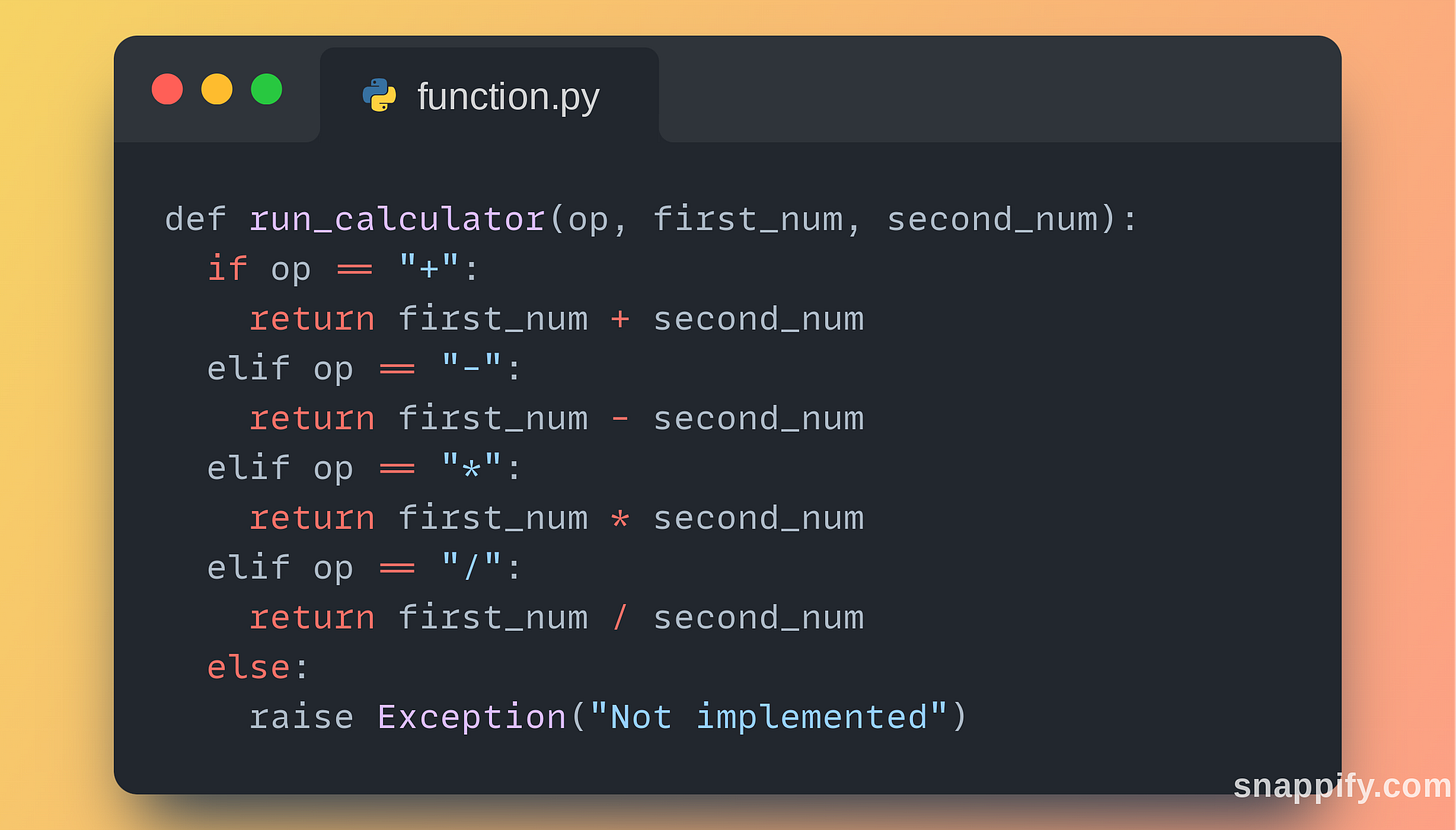

Once you have the values extracted from the LLM response, it is time to call your application code to actually execute this simple calculation. You can use any programming language for this, but here’s a sample code in Python. (Well, I usually pick Python for demonstration as it has a very clear syntax guided by the Zen of Python)

Now that we have our run_calculator function ready, we simply pass the extracted arguments to this function. It returns back the output number 1219216884.

Final Step: Passing the result back to LLM

In the final step, we pass the resulting number of the calculation back to the LLM. At this point, the LLM is expected to take a hint of this result and then continue generating the final answer in a natural conversational tone.

To perform this, we repeat the prompt and the response from before, and append our magic from the Python function after that. For instance, we use:

SYSTEM: You are a helpful chatbot …. In this environment, you have access to the following tool...

User: Tell me what is 12356 times 98754?

Assistant: Sure, to multiply 12346 by 98754, we can use ...

</function_call>

By calling this function, I get back the following output.

<function_result>

<result>1219216884</result>

</function_result>

So, my final response would be:Basically, we keep the system prompt as it is, we keep the user query as it is, but we partially complete the assistant response including the part where it performed the function calling, and then we add an additional part where we programmatically inject the result of the function in a nice formatted way (shown in bold in the above prompt).

This means that when the LLM is trying to complete this statement, it is highly likely that it will autocomplete with “12346 times 98754 results in 1219216884.” or something like that, which is the correct answer.

The Good

Let’s now talk about what’s so good about this function-calling procedure.

The fundamental idea of the function calling technique in LLM is to intervene in the output of the LLM to inject logical flow that can be programmed in a deterministic way. We already saw in the previous post that a RAG technique can be used similarly to inject information to the LLM through prompting. However, in some case, RAG is not possible. For instance, in the calculator example, the user can ask for any number multiplied with any number, and it is not possible to retrieve a relevant multiplication table without extracting the exact numbers of multiply.

Note that, so far we have only added a single function to the system prompt to the LLM. However, you can provide it with multiple function descriptions, and only some of them may be useful for the LLM to answer the query presented by the user. For example, you want to build an AI assistant for stock trading, and you can provide it with two functions:

Given a stock symbol, fetches the current and historical price of the past few days.

Given a stock symbol, fetches the fundamental ratios of the company.

The LLM can now have a technical research tool and a fundamental research tool available at its disposal, and by combining their information it can behave like a human-like stock trading strategy specialist.

Allowing usage of multiple functions increases the capability of LLM drastically. For example, you can now write functions that take a piece of code (say a git command) and executes it. If the code generated by an LLM contains an error, but we can feed the error back to the LLM in the result prompt, such as

Assistant: Sure, to multiply 12346 by 98754, we can use ...

</function_call>

By calling this function, I get back the following output.

<function_result>

<error>SyntaxError at line 2; near 'this', expected '.' but got ';' </error>

</function_result> which tells the LLM what exact error it did. Now, it can recify its errors and retry the function calling again.

If you think about it a bit, this is exactly how we provide feedback to ChatGPT when it does not provide a response that we particularly like. But by using function calling, now no human intervention is needed, and completely autonomously the LLM is able to execute the user request, by using the tools at its disposal.

This brings a new kind of generative AI system, called AI Agents.

And the bad!

However, as with everything, there is a price to pay for all these good stuffs.

First is the high cost associated with this technique. Note that, you will need to send two calls to the LLM here, one before the function call intervention, and another after the function call output to respond back the answer. If you see, both of these send the same system prompt, which also contains tokens describing the functions. This means, on average, you send 2x more tokens in this technique, but approximately 2x more cost.

The second thing is that the more tools (or functions) you want to use, the more tokens are present in the system prompt. It increases latency, and cost and reduces the accuracy of the model since now the model needs to remember a much longer context to make a behaviour. For example: Imagine you are preparing for an exam, it is much easier to remember a single chapter rather than the entire book.

Finally, most of the models have a predefined context window length, i.e., the maximum number of tokens you can pass to the LLM. Since in our daily lives, we may end up using hundreds of different tools for different purposes, it becomes extremely difficult to add more than 10 function descriptions in the prompt, beyond which most of the LLM tends to perform poorly.

One solution to this is to keep the function description in a vector database and pull them dynamically based on relevancy, much like an RAG model. In that way, your prompt never contains more than (say 4) function descriptions.

Conclusion

Throughout a few of my previous posts, we have explored ways about how to make large language models effective and efficient using prompt engineering techniques.

As we understand, the prompt may contain valuable insights for the LLM to act upon, which may also contain some sensitive data injected through modes of RAG or function calling systems. This means, an adversary can create carefully constructed prompts to break the system and inject malicious code into your application. In the next post, we discuss some of these security vulnerabilities and how we can protect against these threats.

Thank you very much for being a valued reader! 🙏🏽 Stay tuned for upcoming posts on the Generative AI series. Subscribe below to get notified when the next post is out. 📢

Until next time.